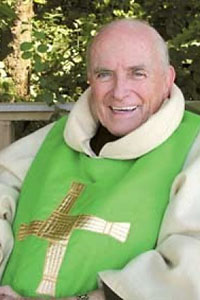

Andrew Greeley,

self-proclaimed “loud-mouthed Irish priest”

On the Relationship between Religion and Imagination

The imagination is religious. Religion is imaginative. The origins and the power of both are in the playful, creative, dancing self.

On the Uniqueness of the Catholic Imagination

A word about the Catholic imagination: Unlike the other religions of Yahweh, Catholicism has always stood for the accessibility of God in the world. God is more like the world than unlike it.

(The Catholic Imagination of Bruce Springsteen)

The objects, events, and persons of ordinary existence hint at the nature of God and indeed make God in some fashion present to us. God is sufficiently like creation that creation not only tells us something about God but, by so doing, also makes God present among us.

(The Catholic Imagination p. 6)

Catholics live in an enchanted world, a world of statues and holy water, stained glass and votive candles, saints and religious medals, rosary beads and holy pictures. But these Catholic paraphernalia are mere hints of a deeper and more pervasive religious sensibility which inclines Catholics to see the Holy lurking in creation. As Catholics, we find our houses and our world haunted by a sense that the objects, events, and persons of daily life are revelations of grace….

This special Catholic imagination can appropriately be called sacramental. It sees created reality as a ‘sacrament,’ that is, a revelation of the presence of God.

(The Catholic Imagination p. 1)

On Stories and Doctrine

Religion begins in the imagination and in stories, but it cannot remain there. The stories which are our first contact with religion… are subject to rational and critical examination as we grow older to discover both what they mean and whether we are still able to believe them. Bethlehem becomes the Incarnation. The empty tomb becomes the Resurrection. The final supper becomes the Eucharist. These are all necessary and praise-worthy developments. Nonetheless, the origins and raw power of religion are at the imaginative (that is, experiential and narrative) level both for the individual and for the tradition. The doctrine of the Incarnation has less appeal to the whole self than does the picture of the Madonna and Child in a cave. The doctrine of the Resurrection has less appeal to the total human personality than do the excited women and the awestruck disciples on the road to Emmaus that first day of the week. The doctrine of the Real Presence is less powerful than the image of the final meal in the upper room. None of the doctrines is less true than the stories. Indeed, they have the merit of being more precise, more carefully thought out, more ready for defense and explanation. But they are not where religion or religious faith starts, nor in truth where it ends.

(The Catholic Imagination p. 4)

On Lyrics, Liturgy, and Witness

So if the troubadour’s symbols are only implicitly Catholic (and perhaps not altogether consciously so) and if many folks will not understand them or perceive their origins, what good are they to the Catholic Church? Surely they will not increase Sunday collections or win converts or improve the church’s public image. Or win consent to the pastoral letter on economics.

But those are only issues if you assume that people exist to serve the church. If, on the other hand, you assume that the church exists to serve people by bringing a message of hope and renewal, of light and water and rebirth, to a world steeped in tragedy and sin, you rejoice that such a troubadour sings stories that maybe even he does not know are Catholic….

Those Catholics who speak to the meaning of life out of the (perhaps) unselfconscious images of their Catholic heritage have a more profound claim to be liturgists than diocesan liturgical directors, for example, who gather to devise ways to use the liturgy to brainwash the laity into accepting the social action views of those who draft pastorals. (I do not know whether the assumption that this can be done is more hilarious than the attempt to do so is obscene.) The Catholic minstrels, such as these may be, are the true sacrament-makers because they revive and renew the fundamental religious metaphors. We must treasure them rather than ignore or denounce them. Or impugn their motives.

(The Catholic Imagination of Bruce Springsteen)

– Andrew Greeley, February 5, 1928 – May 29, 2013