It happened today on my start screen calendar. I watched it flip from Good Friday directly to Easter (tomorrow), with nary a Holy Saturday in between. One of the earliest Christian heresies was that Jesus didn’t really die. There were variations on the theme — he merely swooned, or he was never so human or incarnate or mortal as to be able to manage it.

To be fair, it really is hard to reconcile the fully God and fully human thing with being fully dead and then fully capable of doing something about it. Go ahead and try for a minute; I’ll wait.

There has been much written on the scandal of the cross, but to a large degree, that’s just human nature and divine nature played out to their fullest. Of course if God shows up to restore justice we’re going to crucify him. And of course God will let us.

What’s truly shocking is the day after that, and the day after that. Death and resurrection are the true scandals. That we could stop the pulse of the one who set the planets in motion. That God would come back to us afterward, promising life abundant.

The church calendar doesn’t skip from Good Friday to Easter. It makes space for a great silence, a deep reckoning and wrestling with the consequences of what we have done. The people in Jesus’s life have followed him, loved him, betrayed him, mocked him, and killed him. And today they mourn him.

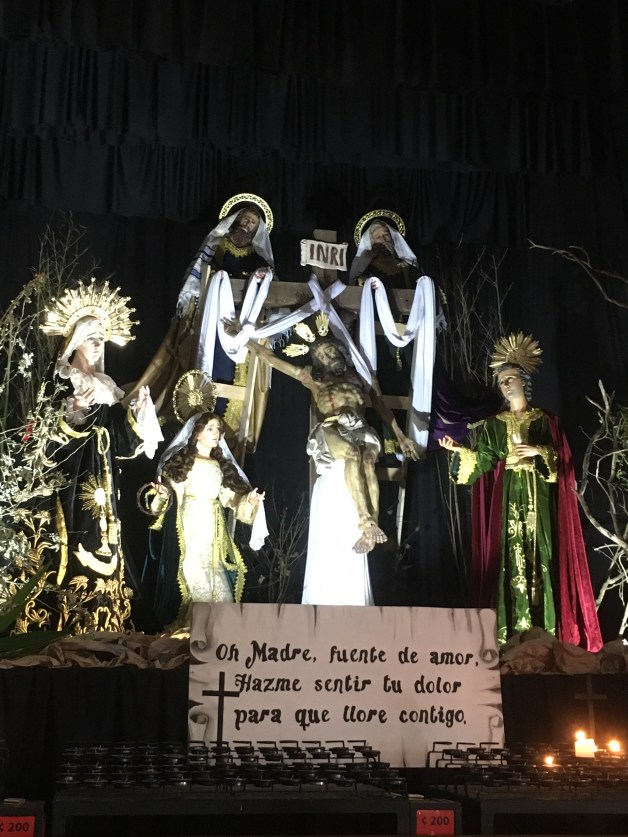

“Oh Mother, fountain of love, cause me to feel your pain, so that I may cry with you.” photo by Jenn Cavanaugh

This Lent, we have walked together alone through unrelenting cycles of grief and confusion. Today we have been given a day to name and mourn our losses, to feel and so clarify our feelings. Sometimes we only recognize what we truly love for what it truly is when it has been taken away from us.

Your absence has gone through meLike thread through a needle.Everything I do is stitched with its color.— “Separation” by W. S. Merwin

This is a season of apocalypse, not in that the world is ending, but in that one superficial layer of it has been pulled back to reveal another layer of depth. What have you seen that you can’t unsee? Make a note of it, because there will be a temptation to snap out of this weirdness and revert to a version of “reality” that merely glossed over what is real.

We are living in a time in which the old has passed away and new has not yet come. For today, let’s just sit here a spell and reckon with it. We might feel like we’re stuck in Stephen King’s novel The Stand (for which he is, apparently sorry), but it’s a line and image from his Pet Sematary that should stick with us now: “Sometimes, dead is better.” We didn’t go through all of this for that kind of twisted at-all-costs reanimation, did we?

This is the time to sift between the habits we miss because they brought consolation to the world and those that simply made us comfortably numb to it.

It’s okay to grieve the loss of normalcy, to admit that it hurts to give up the things that make us happy. I, for one, should be traveling next week, not making sack lunches for homeless teens with nowhere to be during the day.

Or should I?

This is not the fast we would have chosen, but if we can see it through in the spirit of the fast God chooses, then we and the world will ultimately be better for it.

Yesterday we buried our dead. Today we mourn. Tomorrow we will have the holy task of ushering back to life what is worthy of our love and devotion and co-creating the world anew.