“If someone asks, ‘What are these wounds on your body?’ they will answer, ‘The wounds I was given at the house of my friends.’” – Zechariah 13:6

I knew a woman with a wound that had never healed. She came from Kosovo. Ten years before I met her she’d had a procedure to drain a lung her tuberculosis was filling up fast, and the gaping hole it left in her side never closed up. She was perfectly capable of everyday activities, but it affected her whole life. She was beautiful and intelligent, with a mix of stoicism and cheerfulness prized in her culture, but she never married. All her friends and siblings did, including a brother who had suffered a head injury as a child that left him wall-eyed and slow. He had a dozen healthy children and a grandchild on the way. She had a wound that told the story of her life.

Even those of us with wounds that have healed know that every scar has a story. They are mementos of reckless childhoods, of moments in which we forgot our own strength or limitations, of burst appendices, of giving birth. They are physical records of our lives that we carry around on our bodies.

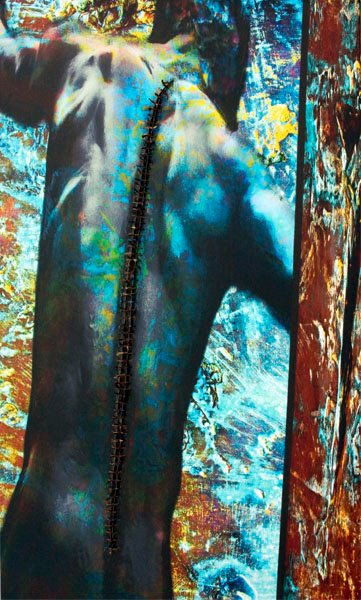

Seattle artist Paul Tonnes has a major abdominal scar from a surgery he was too young to remember to correct a condition he was too young to recall having, and yet his body reminds him. The printed canvases in his series Wounds have all been slashed and stitched together in such a way that the violence done is still visible, even palpable, but the damage is being held together in hopes of healing. The Wounds do not depict the violence – no indication is given of the source of these wounds – as much as the healing process. The palette of the pieces is bold, mottled, and reminiscent of bruising. The stitching is roughly done with twine, utilitarian knots and autopsy needles, some of which still dangle from the canvas as if to acknowledge the work left to be done; others remain worked into the canvas itself as if they are an integral part of the work.

art by Paul Tonnes

Some of the wounds seem old or even postmortem. Did the youthful immortal, sculpted of marble and sporting a Y-incision, suffer from internal injuries? Was cracking his perfect chest the only way to see them? Were they visible even then? One woman’s wounds seem to serve as points of connection to the world around her, as much as sources of pain. Her wounds seem smaller than the others, more like stings. Other wounds are still open and raw, but no blood and guts pour out of them. The openness is a void, a space for healing. Or maybe those are the cracks that Leonard Cohen recognized were present in everything because “that’s how the light gets in.”

Not all the wounds are on the figure’s person. Some are environmental, but the tension of them is felt in the musculature of the Davidic torso and the amorphous body reminiscent of Michelangelo’s Four Prisoners; the poorly sewn gash in the canvas suggests the damaged surroundings in which he’s struggling for the freedom to be fully formed. An Atlas-like figure bends under a burden with a tightly stitched seam. As the artist noted, if the stone had not been repaired, our beleaguered titan would have had half as much to carry, but someone somehow took the trouble to make the burden itself whole. Who does that?

The physicality of these ruptured canvases reminds me of the physicality of Lent. Lent is a time many of us seek to identify and break the physical habits that inhibit our spiritual lives or establish new habits that reconcile our physical and spiritual lives. Sometimes we subject ourselves to things at Lent because we want to get our heads around the harrowing reality of our sins and of Christ’s sacrificial journey to Jerusalem to put them to death in his own body. We suffer graphic and gut-wrenching depictions of the Passion and exactly what happens when a nail is driven through a human hand. We imagine ourselves suffocating. We are people with a violent and physical story. These canvases bring me back to the healing beauty of the cross and the wounds of Christ that are our wounds. Some of these wounds are fresh and raw. Some are emotional scars with stories that have shaped our stories and where we see ourselves in the story of salvation.

Tonnes offers powerful images to sit with during Lent as we consider the violence done to and around us, as we confess and repent of the violence we’ve done, as we present our wounded bodies and souls to the One who offers healing, and as we cultivate the disciplines that will help us continue to do so all year long. Any one of them could be read as a Christ figure. Any one of them could be any one of us.

Paul Tonnes is a Seattle artist working in the mixed media realms of digital manipulation, print, and encaustic. His series “Wounds” consisting of cut and stitched canvases explores the human body’s potential for healing. You can see more of his profound work at paultonnes.com