For Advent, an ekphrastic poem of Mary’s secret thoughts on the annunciation – by Jenn Cavanaugh.

Tag Archives: Poetry

Open Mics, Open Doors: Cultivating Culture and Relationships

“All culture making requires a choice, conscious or unconscious, to take our place in a cultural tradition. We cannot make culture without culture. And this means that creation begins with cultivation – taking care of the good things that culture has already handed on to us. The first responsibility of culture makers is not to make something new but to become fluent in the cultural tradition to which we are responsible. Before we can be culture makers, we must be culture keepers.”[1]

When we start talking about the church acting as a community center or a cultural center, people get understandably nervous. The local church should be much more than a community or cultural center, and those models should not constrain a church’s mission, and yet it must act in those capacities if it is to be both local and the church.

Your neighborhood may be different, but mine has some serious trust issues with “church” in the abstract. Organized Christianity has earned a reputation for bait and switch. Free meals! But I have to listen to someone yell at me about death and hell before I can eat? Welcoming community! Until my work schedule changes and no one notices I’m gone. (Or worse, they do, and hound me to come when I can’t.) Hip music! Followed by half an hour of trying to work through which two-thousand-year-old cultural mores still apply to women. Christians rationalize these kinds of disconnections on a regular basis, but we need to hear these disjointed messages as our visitors do. These scenarios come off as false advertising at best and intentional deceit at worst.

Why are there so many strings attached to the things we do in Jesus’s name? It communicates that we see the gospel as such a tough sell we have to lure people into the salesroom with a gimmick. In the words of R.E.M. “What if we give it away?”[2] What if we fed people simply because Jesus himself invites us to and tells us he’ll be on the receiving end of anything we give? What if we applied our shrewd-stewardly stratagems toward working out how to make the most of our resources to care for others more comprehensively, not how to get more out of them in return? To the degree that our churches have tried to sell and barter the words of life entrusted to us freely, we must own responsibility for the numbers of people who have chosen not to buy in to the churched life.

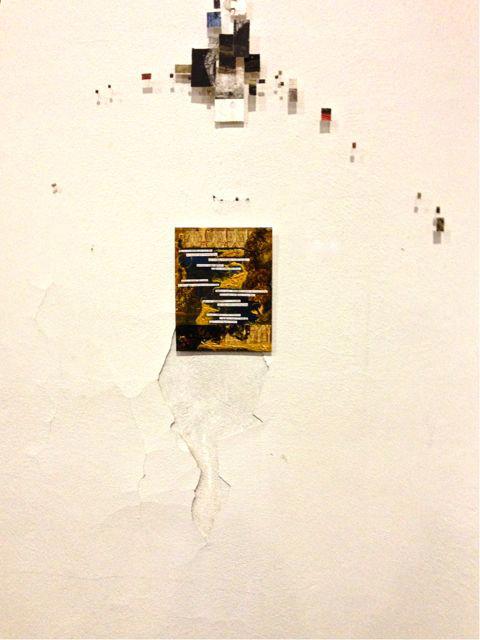

“Shelter?” by Heidi Estey. This was our poster monster for an outdoor group show in which almost all the pieces were eventually “taken in” by passersby – part of why we now put together our outdoor shows with in-house artists aware of such eventualities.

Considering ourselves, our traditions and our assets to be cultural and community resources would correct our attitudes substantially. A church, building and people, should be a blessing to its parish. The whole Judeo-Christian story we find in scripture is about God forming a people set apart to be agents of blessing to the rest of the world. To be chosen does not mean that we are in with God and the others are out; it means we are the ones called to invite the others in. This has nothing to do with imposing our lifestyle on others and pressuring them to conform to an enlightened Christian culture so they can know God like we do. It has to do with welcoming them in a way that communicates God’s desire to be known by them, creating buffer zones in which to hear that quiet voice, and making room amongst us for those who choose to follow it.

Few of us had any say in the physical design of our meeting places, but the onus is now on us to make them convey welcome. Our church is by far the churchiest looking church I have ever been a part of. Those of us moving in after years of worship in a movie theater and an office building suffered some serious culture shock. It’s an extremely staid and solid red brick and stained glass affair. Approaching from the front all you see are concrete stairs leading to three massive sets of wooden double doors. The view most often seen from the street is of these six immense and eminently closed doors. It’s imposing. I’ve been going to church all my life and I can hear these doors slamming shut just looking at them. The transformation when those doors are all flung open is supernatural, especially at night with warm light and music and voices pouring out onto an otherwise dark street. Suddenly it’s inviting. All the connotations of sanctuary make sense again. Strangers pop in just to say how happy they are to see the doors open.

The openness of our doors has become hugely symbolic for me. The unfortunate reality is that the cavernous open space behind those doors is an absolute bear to heat. In July and August it’s a relief to have the doors open, but almost any other time of year it’s a sacrifice. If you come to worship with us in February you will find one of the six doors propped not quite half open. If you’re fifteen minutes late the only thing holding that door open will be a tripped one-inch-wide deadbolt. We have bass and drums and lots of porous windows so if you walk by you know something’s going on, but it’s hidden behind essentially closed doors. Suffice it to say, I think any excuse to open those doors that’s not antithetical to the gospel is a good excuse. If it’s an activity that blesses our neighbors, meets needs in the community, or helps us fulfill our commission as cultivators of creation and creators of culture, so much the better.

Cultivating culture is different than conserving culture. Whether or not we avail ourselves of them, the Church on the whole has done a fine job of conserving its cultural goods: the writings of the first bishops, medieval mystics and the Scholastics; the stories of Asian martyrs; the paintings and sculptures of Michelangelo and treasured Orthodox icons; the chants heard morning and evening for centuries throughout Europe. If we only conserve culture, though, the Church will function merely as a museum. The Church is a unique institution called both to conserve and create, and as such, must be continuously reinventing the priestly ministry of representing humankind to God and God to humanity while consciously maintaining a tradition that runs back through the apostles and the patriarchs to our creation in the image of the Creator and Ruler of all. We who have historically been at the forefront of movements to recreate and reorder society have abdicated our responsibilities. Neither conservatives who commit to structures simply because they exist nor radicals who reject the very idea of structure that makes creative life sustainable are embodying the image of God or serving as Christ called us.

As cultivators we watch for the new growth peeping up from the earth around us, determine whether it’s the genuine article or a choking weed, and nurture the good growing things around us. We look for the plants in need of particular care, especially those good for food or medicine, and tend to their specific needs. As a Christian and as a poet, when I look around, one area of the garden that I see failing to thrive that I would like to help maintain for my culture is the thoughtful use of words. Dana Gioia wrote a fabulous essay called “Can Poetry Matter” in which he talks about the decay of language and discourse and offers six concrete suggestions for bringing poetry back into our public lives as a corrective to this decay.

I borrowed three of his ideas and distilled them into one event that answers our corporate call to be cultivators of what’s beneficial to our society and serves as yet another reason to have the doors open. Due to an ongoing failure of imagination, we called it a no-mic open-mic community reading, although Literary Potluck might stick eventually. We would call it a read-in, but that makes it sounds like we’re protesting something. Like an open mic, people can sign up ahead of time to read. Based on one of Gioia’s suggestions and our congregational ratio of significantly more readers to writers, we invite people to read either their own work or something they’ve read recently that they would like more people to hear. Open mic audiences tend to consist of writers there to read and close friends of writers there to read. They don’t draw a wide audience and the tenor of the events generally vibrates between ego and nerves. With this format anyone can participate and we all hear a lot of great writing. We also tone down the pressure to perform by removing the actual microphone from the scene. The first time we planned one of these we were a small enough group we could sit in a circle at the back of the church. The next time we set up a small table in the aisle in front of the last few pews. A microphone was not necessary to be heard.

As we held the events on Arts Walk nights we made sure people had easy access so they could sit or stand and listen a while and feel free to leave. Readers have ten-minute slots, but we ask them to keep individual readings to five minutes or less, so there are plenty of opportunities and to slip in and out without walking out on a reading. The Arts Walk is three hours long, so we took frequent breaks for coffee, tea and snacks people from the church brought to share and just to talk, catch up with other and meet anyone who came in during the reading.

[1] Andy Crouch, Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (Downers Grove, Ill.: InterVarsity Press, 2008), 74-75.

[2] Mike Mills, William Berry, Peter Buck and Michael Stipe, “What If We Give It Away?” Life’s Rich Pageant (I.R.S., 1986). From the first verse and chorus:

On the outside underneath the wall

All the money couldn’t buy

You’re mistaken no one’s standing there

For the record no one tried

Oh I try to…

What if we give it away?

For years this chorus would begin to play spontaneously and, as it turns out, prophetically in my head as a response to that hard sell mentality. Our first outdoor gallery initially felt like a bust. It was the only time we issued a call for submissions and got nothing of artistic merit from the outside world. It was raining so hard we almost cancelled the show because it was so miserable to install. Then a friend of one of our artists showed up with a couple of nice pieces. It lightened to a typical Seattle drizzle by the time the Arts Walk started and we had a good time hanging out on the sidewalk with our umbrellas and loaning them out so people could peruse our quirky little installation called Shelter. Half the pieces disappeared over the weekend. An editor of a local arts magazine happened on it during that time and mentioned to a mutual friend that he was debating whether or not to take a piece home as well, and an important conversation about public art, gift culture, and the church ensued. My friend referenced that same line (“What if we give it away?”) when he emailed me to say it sounded like the church was doing something right.

Advent Week 2: Waiting for Peace

Another tough week. A week of violence and revelations of violence and of just how deep the violence of the so-called good people of the world runs.

Thankfully the same scripture that instructs us to seek and receive peace, which seems so far removed from our world right now, also discourages us from faking it, from pretending the wounds aren’t so bad and spouting nonsense about peace when there is no peace. We of all people should trust neither in political promises of security nor in our innate collective goodness to one another to eventually win out. The kind of peace we can drum up ourselves doesn’t require waiting. It tends toward immediate gratification (taking whatever pacifies our desires) or mollification (caving in to other’s illegitimate demands) or diversion – gorging our senses to overwhelm our sensitivity to one another’s needs, eating to the point where we can no longer imagine starvation, turning up our own personal soundtracks so we don’t hear the suffering of others, looking at anything as long as it is away.

The sense of shalom peace that courses throughout the words of Genesis and Jeremiah and Jesus entails relational wholeness. None of us can achieve that kind of peace alone. It has nothing to do with getting away from it all and everything to do with assuming rightful places within a righted all. It is a peace we receive from drawing near to a God who would suffer the violence of birth and death to be with us. It is a peace we seek for our cities and neighbors as we strive to do right by one another.

from “Here on Earth”

The old man living

In his rented room

Grows lonely as the night comes on

Especially in winterAnd the boy shooting drugs

On the tenement roof

Is lonely whether or not

He has companionsLovers lie sleeping

Side by side

A wilderness between themAnd their unborn infant

Is already alone

So soon to be discarded

Even as he begins

Unfolding in the womb

Of his lonely motherBecause the scatterer

Has overtaken us

Betraying promises

Estranging loversTearing us inwardly

And tearing us apart

One from anotherAnd this is why

Those of us who are sated

Find it so easy to ignore

Those of us who are starvingAnd why we have been known

To torture one another

Why there are times

When we are far more cruel

Than the animals.Nevertheless

Taken all together

Or taken one by one

We are the holiest

Of all earth’s creaturesFor he who kindled

The fire of the sun

He who draws out the tender leaves

From the dark twigs of winterHe who has whittled

A cabin for the snail

Has also carved our names

In the palm of his handAnd he became a child

The better to be near us

Born in the wintertime

Born on a journey….– by Anne Porter, from Living Things: Collected Poems (New Hampshire: Steerforth Press, 2006), p. 124.

Advent Week 1: Waiting with Hope

[Rediff] Racisme et militarisation: la face cachée de la police américaine

lemonde.fr/les-decodeurs/… // http://t.co/4dxRzBF0yb—

Le Monde (@lemondefr) December 04, 2014

It’s been a bad week to be told to wait.

An especially frustrating – even demeaning – time to be told to wait for justice, for the world to be set right, that things will get better, things which are not entirely in our hands to fix, things that can only truly change through some odd and mystical combination of patience and systemic upheaval, accountability and radical forgiveness, quiet and cataclysm.

Waiting with hope is the antithesis of an escapism. Waiting with hope does not mean blithely ignoring or submitting to the status quo, but walking humbly enough to find oneself in the company of those most deeply threatened by it, who have no choice but to wait, because their lives depend on others acting justly. That’s deeply unsettling when you think about it: living at one another’s mercy. We all do it, but it’s a gamble with blatantly rigged odds. Sadly we don’t extend kindness or even the benefit of the doubt with anything resembling equality and no one is under any illusion that we can rectify that overnight. And so we wait, but in the hope that justice will be established, that power will protect the powerless, that the starving will have their fill of good things. We wait with those who wait. “You’re tired. But everyone’s tired./ But no one is tired enough.” So…

Wait

Wait, for now.

Distrust everything if you have to.

But trust the hours. Haven’t they

carried you everywhere, up to now?

Personal events will become interesting again.

Hair will become interesting.

Pain will become interesting.

Buds that open out of season will become interesting.

Second-hand gloves will become lovely again;

their memories are what give them

the need for other hands. And the desolation

of lovers is the same: that enormous emptiness

carved out of such tiny beings as we are

asks to be filled; the need

for the new love is faithfulness to the old.

Wait.

Don’t go too early.

You’re tired. But everyone’s tired.

But no one is tired enough.

Only wait a little and listen:

music of hair,

music of pain,

music of looms weaving all our loves again.

Be there to hear it, it will be the only time,

most of all to hear

the flute of your whole existence,

rehearsed by the sorrows, play itself into total exhaustion.– Galway Kinnell

from Selected Poems. © Houghton Mifflin, 1983

Pantoums

Despising the Pain: A Pantoum by Jenn Cavanaugh

I face death every day

For the joy that is set before me.

Dust returns. Death loses the fray –

The happy end begins the story.

For the joy that is set before me

I ride the eternal like a tide.

The happy end begins the story –

We’ll wear our spirits on the outside.

I ride the eternal like a tide,

Dizzied and spun, despising the pain.

We’ll wear our spirits on the outside

For the work that is not in vain.

Dizzied and spun, despising the pain,

Dust returns. Death loses the fray.

For the work that is not in vain

I face death every day.

Poor blog, doomed respository for my second-tier poems. I post this one as an example to accompany yesterday’s Writers Workshop post on the pantoum form, so you can see what you can get out of working in the form in short order. It’s only the third or fourth one I’ve ever written, and the results still feel blocky, compared to writing in unrhymed free verse. If you get something out of the theme or a phrase, I’m glad. Otherwise, this is what a writing exercise looks like!

So far, the best part of writing pantoums is that they practically write themselves – you put a couple of lines together, give them a flick, and you have a perpetual motion poetry machine. For me, they are line-generators. You put a line in, you get a line out, because the form is going to take you there. To write one that stands up as fine poetry, like the one I’ll leave you with here, I will probably have to give up the rhyme, as she did, make my lines more grammatically creative, and incorporate more narrative detail. A pantoum doesn’t have to tell a story, but the ones that appeal to me most suggest one. Do you have a favorite or one of your own to share?

Stillbirth by Laure-Anne Bosselaar

On a platform, I heard someone call out your name:

No, Laetitia, no.

It wasn’t my train—the doors were closing,

but I rushed in, searching for your face.

But no Laetitia. No.

No one in that car could have been you,

but I rushed in, searching for your face:

no longer an infant. A woman now, blond, thirty-two.

No one in that car could have been you.

Laetitia-Marie was the name I had chosen.

No longer an infant. A woman now, blond, thirty-two:

I sometimes go months without remembering you.

Laetitia-Marie was the name I had chosen:

I was told not to look. Not to get attached—

I sometimes go months without remembering you.

Some griefs bless us that way, not asking much space.

I was told not to look. Not to get attached.

It wasn’t my train—the doors were closing.

Some griefs bless us that way, not asking much space.

On a platform, I heard someone calling your name.

Writers Workshop: Pantoum

PANTOUM

A pantun is a traditional Malay form of quatrain-based poetry. Victor Hugo introduced it to France in 1829, calling it pantoum. The westernized pantoum descended from a specific form: pantun berkait, which repeats whole lines in an interlocking pattern. The second and fourth lines of any stanza become the first and third lines of the stanza that follows. In the pantoum's last stanza, the first and third lines of the opening stanza are finally repeated as the fourth and second lines. The order of those lines can be reversed, but ideally a pantoum will end with the poem's opening line, creating a kind of circle. Pantoums are not required to rhyme, but most do. They can vary from two stanzas to as many as you wish to write.

Composing a pantoum is a great writing warm-up. You first write a stanza of four lines. The pantoum will work best if the lines are fairly intact, evocative phrases of similar length or rhythm -- each expressing just one basic idea or image that can resonate in different ways when placed in a new context, as they will be throughout the poem. Most of your work in setting the tone and sense goes into laying this foundational stanza, because by the second stanza, you’ll see the poem start to take on a life and significance of its own, while you just follow along or nudge it into shape with an additional line here and there. Allow the wave-like quality of the form to carry you along. Be spontaneous. Allow for happy accidents and juxtapositions. Once you get to the end you’ll probably need to go back and edit a couple of lines to fit into the rhythm that’s developed. This form demonstrates the power of the line. If you have an old poem lying about that isn’t working, but some of the lines are keepers, or an orphaned line running through your head, start a pantoum with one of those lines. This works especially well for couplets that start to sound a bit sing-songy; the pantoum form aerates them – giving breathing space between the rhymes and finding depth in the repetitions. This also works in reverse, as your pantoum might generate one perfect line that starts a whole new piece. Writing a poem in any form is a challenge. Give it what you have today. There might be a glaring hole or clunky line that you know you need to come back to. Start a new project and go back to this one next week when you can hear the poem as a whole with fresh ears and respond accordingly. Getting started is as easy as copying and printing the form below. Stuck for a first line? Scroll down further for some ideas there. Make it rhyme ABAB and it will start writing itself after that.

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 1)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 2)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 3)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 4)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 2)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 5)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 4)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 6)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 5)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 7)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 6)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 8)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 7)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 3)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 8)

_________________________________________________________________ (Line 1)

I find this a very meditative form. The wave-like structure encourages movement in place, like something caught in the tide just off shore. The water churns up deeper layers, but by definition you end up where you began. You swirl around a thought until you come to rest. If you have a phrase, mantra, or story that just won't let you go, maybe it's a pantoum.

When I introduced this form at church for a Lenten devotional writing class, I suggested starting with a biblical phrase...

Ideas for opening lines/ texts:

“Dust you are and to dust you will return”/ Genesis 3

“Do not put the Lord your God to the test”/ Matthew 4

“[And afterward] I will pour out my spirit on all people”/ Joel 2

“This inheritance is kept in heaven for you”/ 1 Peter 1

“Revive us, and we will call on your name”/ Psalm 80

“You will be like a well-watered garden”/ Isaiah 58

“Work out your salvation with fear and trembling”/ Philippians 2

“It is written about me in the scroll”/ Hebrews 10

“He loved them to the end”/ John 13

“She has done a beautiful thing to me”/ Matthew 26

Give it a try! I’ll post the results of my writing exercise tomorrow, as well as a much finer example.

To the Tune of “The Lilies of the Covenant:” A Psalm 80 Haibun

To the Tune of “The Lilies of the Covenant:” A Haibun

by Jenn Cavanaugh

(Yesterday I posted about the haibun form. I wrote this one for our church’s Lenten Devotional to accompany Psalm 80.)

Restore us, O God

make your face shine on us

that we may be saved

– Psalm 80:3

Scripture often compares us to grass, to flowers, to trees. We are plants of the field, of the garden, of the wilds – rambling, bristling roses; burning, flowering bushes; a host of succulents storing water in the driest deserts; swaying oasis palms flagging hidden sources of water; tumbleweeds that mark the sand and frame the next generation of climbing plants. We sprawl through the wilderness toward a land of streams, a land cleared of everything that doesn’t yield fruit.

Consider the vine

without fangs or teeth or arms

it survives nations

The strength of a vine is its tenacity in springing back, in adapting to the place it is planted. The terms of its survival are unconditioned – a mark of the people of the God who preserves and glories in faithful remnants. The vine’s response to being trampled is to renew its grip on the good earth, anchor itself with the buried tendrils, and keep growing. When cut back mercilessly, the broken bits form new shoots. The vine’s long stems are designed to break new ground and cover it, not to stand on their own. One lonely strand epitomizes the frail, but as a whole it establishes itself in heaps, disregards artificial limits, surmounts impediments, drapes itself lightly over inhospitable terrain, and clambers toward the sun at every opportunity.

- Photo by CameliaTWU/ Creative Commons http://www.flickr.com/photos/cameliatwu/3992092192

Rooted in motion

Runners commit to earth and sky

Morning glory

Writers Workshop: Haibun

Once or twice a year I’ll put together a guided writing workshop for our adult education time at church. I’ve found that introducing different forms and themes each week limbers us up to experiment with something new and gives us a nudge to get started rather than staring at blank sheets of paper. No one feels the need to write something expert in a form they’ve never encountered before or on a subject they just started thinking about five minutes ago. The writing is fresher, and people are consistently surprised by what they come up with. I think I have enough material to share at this point that I’ll make my intros to these forms and themes into their own “Writers Workshop” category.

The haibun form combines haiku and prose poetry. Originally it was a form of travelogue or journal writing. Writers pause in their poetic narrative or description of an event, person, place, or thing to compose a haiku that captures the emotions of their experience or encounter. The effect is that of a transfer of memory, whether real or imagined. The descriptive narrative evokes the senses with concise, poetic langauge, usually in the present tense, drawing the reader into a dreamy immediacy. The haiku functions to further the narrative or comment on it through summary or juxtaposition. Good haibun, like haiku, favors impressionism over abstraction. Don’t muse about how children grow up and leave us. Tell me about how your hand, now stuffed in a pocket, used to be both colder and warmer holding hers in this park. Then show me the indentation in the grass of the empty nest.

There are many examples to be found at Contemporary Haibun Online, and I’ll post one I wrote tomorrow.

Epiphanies Part 2: …And Where It Settles

Click here for Part 1.

Epiphanies have to do with seeing, in the deepest sense. A spotlight comes on and shines on something that has been there all along and, as if for the first time, we truly see it. The work of the artist is to train one’s eyes to see and communicate it such a way that others see it as well, to witness and bear witness. Flannery O’Connor wrote, “Your beliefs will be the light by which you see, but they will not be what you see and they will not be a substitute for seeing.” We require light to see, which is why light is a primary metaphor for describing epiphanies: realizations come to light, connections are illuminated, and so on. Following Christ in the world depends heavily on having eyes to see and ears to hear. Artists have a particular calling to make what they see visible to others, but we are all called to live as witnesses – to see and hear and make what sense we can of God’s presence, action, and guidance – and to respond accordingly.

A quiet consensus has formed in this show – that the light by which we see enters through the cracks and crevices and that it settles, well, just about everywhere, really – everywhere we have trained our eyes to see and taken the time to look. Poet Mike McGeehon sees the light settling in the enforced pause of disparate souls at a stoplight.

In all of us here

in the 40-second meeting,

settling into our seats

for a moment together

where the intersection is.

– from “Where the Light Settles”

by Mike McGeehon

Photographer Leslie A. Zukor has a theophany by the natural light of the natural world

while Ron Simmons digitally enhances his photographs to reveal the prismatic refractions surrounding saints making visible all the colors hidden in the light itself.

Alison Peacock sees a heavenly father in the earthly. The young Seeker in my poem and in the beautiful collage Trisha Gilmore created for her knows God’s presence before she can articulate it in

the cheek-roughness… of this… tree I can’t name… but… I will someday

– from “Seeker” by Jenn Cavanaugh

in Mars Hill Review 22 (2003)

Autumn Kegley paints her revelling revelation of the joy-filled life. Karla Manus encounters such a life and sees her relatively comfortable, joyless self in stark relief. Elizabeth W. Noyes returns again and again to the return of the full moon in which she catches sight of “infinite possibilities for echoing what is poetic, magical, mysterious and whole in the human heart, and mine.”

In curating this show, I’ve recovered a season. Between the times in which we wait for God to come and prepare for God to act, we have been given a time to train our senses to recognizing God’s presence and present work among us. In the years to come, Epiphany will be for me a time to focus on seeing God in the world, recognizing Christ in others, and becoming more receptive to the connections the Spirit makes.

The Epiphanies group show will be open at Capitol Hill Presbyterian Church of Seattle until February 14th. You can call the church office to make an appointment to see it during a weekday, join us for a service: Sunday, 2/10 @ 9:45 am or Ash Wednesday, 2/13 @ 7 pm, or drop by during the Capitol Hill Arts Walk, 5-8 pm, 2/14. See our Facebook page for more information and pictures http://www.facebook.com/CapHillPresArts

Epiphanies Part I: How the Light Gets in…

About twice a year our church’s arts group plans a themed group show. We identify a theme that corresponds to an upcoming liturgical season or sermon series, send out a call for submissions, offer prizes so modest they hesitate to call themselves that, and work with what comes in. If you’re looking for a creative faith-building exercise, I recommend the practice.

Our current show is “Epiphanies,” in which eleven artists and poets reflect on those a-ha moments of connection, recognition, realization, and revelation. Now that it’s all put together, though, a secondary theme seems to be emerging: Cracks. The chorus of Leonard Cohen’s “Anthem” runs

Ring the bells that still can ring

Forget your perfect offering

There is a crack in everything

That’s how the light gets in.

For me this show has become about how the Light gets in and where it settles. Cohen’s chorus has long been a favorite of mine and our friend Matt Whitney alluded to it while he was installing his piece which uses the various textures of sidewalk cracks to form a received word.

Next to it we posted a poem of mine in which the tears and fissures that threaten our faith become themselves a source of hope.

Miss Vera Speaks

They ask how she grin through that face with that life.

I say I’s never shielded from nothing

‘Cept dying young.

People deep bruised by something

Talk like the world should end.

Won’t catch me dying every day like that.

‘Cause I seen them once

Just once – the cracks in the universe –

Thought I’d fall right through.

‘Stead I laughed – said some kind of God

Put up with a tattered-old place as here

Gotta have some grace for me.

– Jenn Cavanaugh

(originally published in America Magazine in 2007)

When it comes to hanging these shows, we often find ourselves strategizing about how best to disguise the myriad holes, blemishes, and outright failings in sanctuary plaster. At the artist reception on Sunday I was joking about how the condition of the walls was starting to inform our artistic decisions overmuch, and a few of us got looking at this tableau:

Photo by Elizabeth W. Noyes. “She Crawled Like You Out of the Wreckage” by Carrie Redway. “Swarm” by Robroy Chalmers. “Wall” by Church + Use + Time

This patch of wall we’re usually so anxious to conceal became part of this piece by Carrie Redway about the Fall and Eve’s anguished banishment from Eden and of the permanent installation by Robroy Chalmers that speaks to our congregation so eloquently and wordlessly of the Spirit’s movement in our midst. Our church building has been in continuous use since 1923. That wall has come by its imperfection honestly. Why hide it? Why not let it inform our artistic decisions?

More next week…