Click here if you missed part 1

Any theology of culture will intertwine with an interpreter’s rational, theological, and ideological characterization of the present condition of humanity. If culture is a uniquely human creation, its status relies on our status. Does the image of God within us validate our good creations? Does our fallen state taint our works indelibly? Does our redemption transfer to the work of our hands and minds? Most theologies of culture cite the incarnation as a model. If Christ took on flesh and lived among us, we cannot follow God in the abstract or love our neighbor in only an otherworldly sense. In fact, the Trinity as a whole, not just the second person, exemplifies God’s commitment to humanity. God created, entered, and remains at large in this world and has commissioned and empowered the Church to walk to the ends of it to communicate that good news. Turning our back on the world is not an option for Christ’s body.

This is not to say that Christians should not be discerning consumers. Discernment is a constant process that constitutes a major portion of the Christian’s job description. This discernment process, however, occurs within the Christian community, not by forcing our vision on those outside of it. Ralph C. Wood advises we become “self-critical citizens of the world as well as self-critical confessors of the Faith.”[1] We learn to critique our cultures because, like it or not, they define a significant portion of our selves. If Christ did not come to condemn the world, why would he send us poor souls to do so? Or, as Paul once put it to the Corinthians, “What business is it of mine to judge those outside the church? Are you not to judge those inside?”[2] American Christians need to stop trying to enforce “Christian values”[3] outside of the body of Christ. If we concerned ourselves as much with keeping the Church and our own self-righteous selves on the straight and narrow as we currently do with perfect strangers who happen to act or sing for a living, we might wake up one morning to find we have a credible witness in the world.

When we come to terms with and gratitude for the fact that God has set us in our extended human families for our own good and for theirs, we begin to create within our cultures in order to bless them, rather than to curse. We stop trying to protect our own religious sensibilities and God himself by creating a safe cultural ghetto for ourselves. We can describe all our work in the world the way Tim Foreman of Switchfoot describes his band’s music: “Christian by faith, not by genre.”[4]

The apostle Paul validated what he found valid in the Athenian worldview, but sought to enlarge and inform it. He served the Corinthians by becoming like them to win them over, for the sake of the gospel.[5] The Church has traditionally patronized and sponsored the artistic tendencies of high culture. Christians approve what is excellent, see nature (including human nature, in the form of the conscience) as a source of general revelation, and accept that what is true, beautiful, and good in human life represents God’s pervasive, common grace within all creation. We can comfortably affirm ennobling tales of self-sacrifice, and the sentimental images, captured in oils, of devoted parents or a glowing sunset as echoes of God’s presence in our everyday lives. But what about Skins, Grand Theft Auto, and Here Comes Honey Boo Boo? What of the superficial and frivolous, the gaudy and offensive? Should we consume such things? Contribute to their creation?

Not all the ideals of our culture will reflect our ideals, but our convictions of how things should be should not blind us to how things are. We must become conscious of the forces at work and play in our popular cultures that shape us or attempt to shape us. Being aware of the rules and ethos of Survivor, for example, allows us to recognize and resist social currents that might otherwise carry us along to unthinking engagement in behavior antithetical to the gospel. While the language of voting people off the island, dismissing the weakest link, and pursuing entirely wrongheaded notions of winning becomes ingrained and normalized in our collective psyche, those in discerning Christian communities remind each other that the people of God are called to live into a different reality. What if Christians created everyday culture that reflected that reality? How can we do that if we’re not familiar with our culture as it actually exists? What if we occasionally took our kids to an “inappropriate” but important movie and talked to them about it instead of forbidding them to go? What if we listened to their music with them instead of insisting they turn it down or investing our energies in keeping them culturally ignorant? Once a week ask them to play you something and help you hear or see why it is significant to them.[6]

We all have different tastes. I’m not suggesting we feign a fondness for Glee where none exists, but do I become a better witness among my neighbors and co-workers by flaunting my complete ignorance of a show that informs and influences their lives? Dick Staub counsels us to be “serious about faith, savvy about faith and culture, and skilled in relating the two…. Culturally savvy Christians follow the path of neither the cultural glutton nor the cultural anorexic. Instead, they are marked by their discretion and thoughtful discernment.”[7] Discernment is a form of wisdom Christ offers his Church through the Spirit to enable us to walk well in a world full of falling hazards and diversions. It is a gift and a tool that we become more adept at using as we practice it. Much of parenting consists of equipping our children to make good decisions then allowing them the freedom and responsibility to do so. God parents us in much the same way. We need to develop lifestyles of prayerfully listening to the Spirit to rightly and readily discern how to relate to particular aspects of our cultures, but God’s word equips us with some basic principles. Staub summarizes the relevant guidelines in Paul’s letters to the Romans and the Corinthians: all things are lawful, but not all are beneficial. We are not to be controlled by cultural goods or to use them to occasion another’s fall, but rather to do everything we do to the glory of God.[8] We are to remain in conversation with people who do not believe as we do. “Be wise in the way you act toward outsiders; make the most of every opportunity. Let your conversation be always full of grace, seasoned with salt, so that you may know how to answer everyone.”[9] Which response best stimulates that kind of conversation: “I don’t watch that show/ play that game/ listen to that music because I heard it was evil” or “I watched/ played/ listened to that a couple times, but I was so turned off by the glorified violence/ portrayal of women as objects/ the racist-sounding lyrics I just stopped. You obviously follow it more closely than I do, though. What about it appeals to you? What am I missing?”

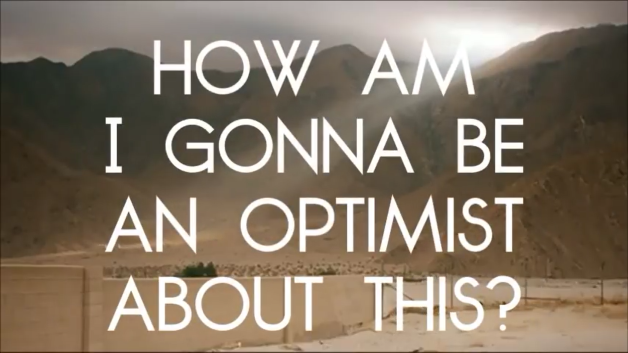

Sometimes our neighbors and co-workers diversions will be just that: diversions – opportunities to check out from real life. Let’s not read too much into those or pretend we don’t have our own indefensible diversions. People who consistently try to convert others to a favorite movie or band or sport, however, have probably found something that moves them and relates to their desire for more out of life. In Your Neighbor’s Hymnal, Jeff Keuss talks about pop music as one of the many cultural forms in which we may find spiritual solace or expression; chances are our neighbors already have.

“True, there is pop music fandom that draws people into the trivial and mundane just as there are some Christian worship services that celebrate consumer culture more than critique it or provide an alternative. But the drive to find something larger than ourselves and make it public is a starting point – even a shallow faith is better than no faith at all. And in this we are to celebrate rather than too quickly denounce the fanboy faith that permeates the culture around us. Our neighbor’s hymnal is filled with pop songs that are sowing the seeds of faith and pushing for a form of life that is larger than the mundane and points to a transcendence worth paying attention to.”[10]

If we dismiss out of hand the cultural texts and goods that God may use to open our neighbor’s heart to something beyond this world, we squelch the prospect of discovering an addition to our playlist that works similarly on us; worse, we hazard quenching the Spirit, who – as the old song goes – moves in mysterious ways.

[1] Wood, Contending for the Faith: The Church’s Engagement with Culture (Waco, Tex.: Baylor University Press, 2003), 102.

[2] 1 Corinthians 5:12.

[3] Whatever those are; the fact that Christians can’t agree on them doesn’t bode well for their universal legislation anyway.

[4] qtd. in Andrew Beaujon, Bodypiercing Saved My Life: Inside the Phenomenon of Christian Rock (Cambridge, Mass.: Da Capo), 42.

[5] 1 Corinthians 9:9-13

[6] This will be a test, by the way. If they put themselves out to articulate something that matters to them and you only find fault with it, don’t expect them to play along next week. Even if a song or video turns you off completely, listen to your child’s heart and how media speaks to it and affirm that heart. Also, don’t expect their articulation to be particularly articulate or convincing at first. By having these conversations you may be giving them their first lessons in putting their spiritual lives into words; they’re not learning this in school. Listen for opportunities to augment their vocabulary for discussing soul issues without putting words in their mouths.

[7] Staub, The Culturally Savvy Christian: A Manifesto for Deepening Faith and Enriching Popular Culture in an Age of Christianity-Lite (San Francisco: Jossey-Bass, 2007), 1, 151.

[8] ibid. 152-153.

[9] Colossians 4:5-6, TNIV.

[10] Jeffrey F. Keuss, Your Neighbor’s Hymnal: What Popular Music Teaches Us about Faith, Hope, and Love (Eugene, Ore.: Cascade Books, 2011), 22.